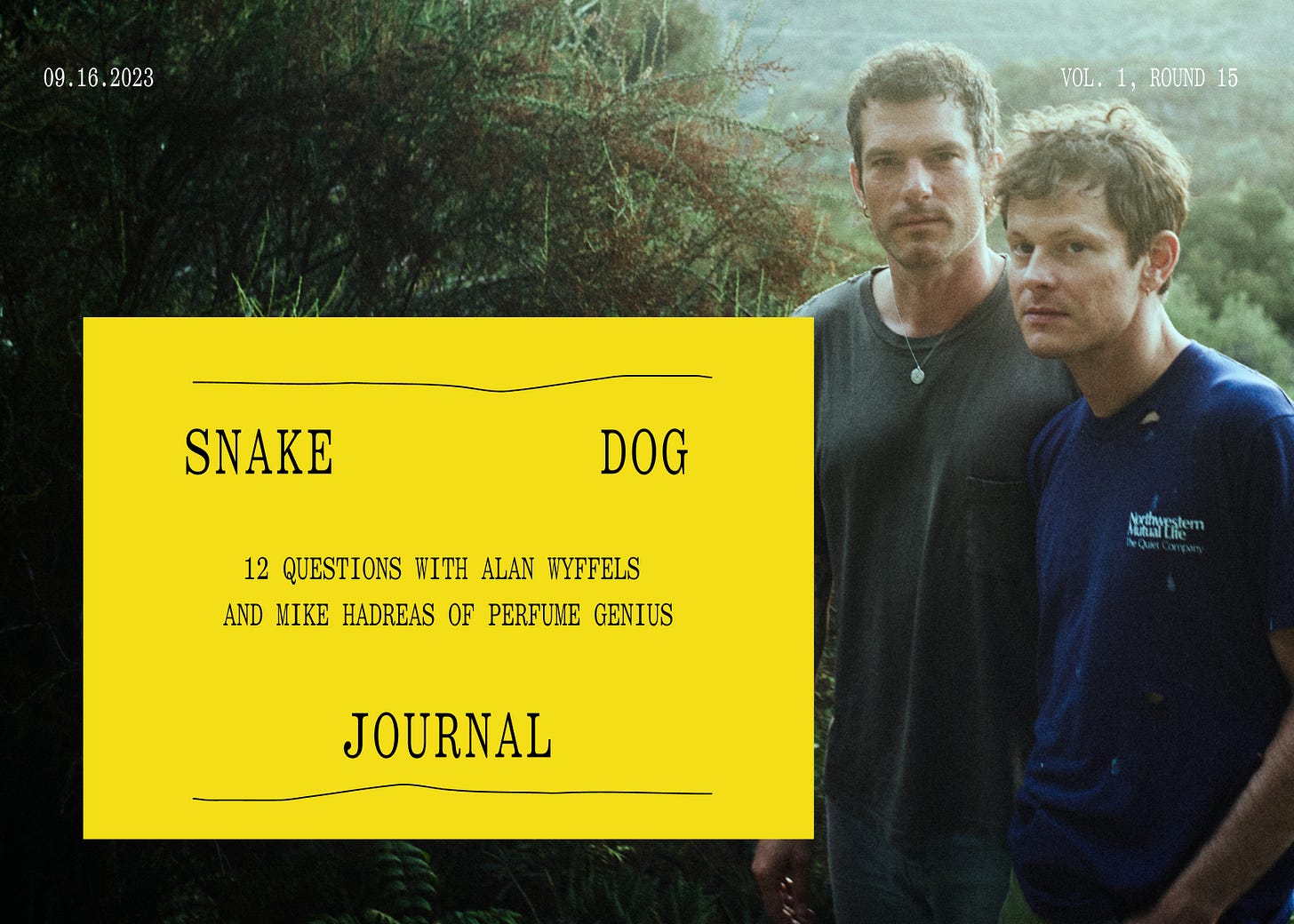

Mike Hadreas and Alan Wyffels are partners in life and work. They live together. They tour together. They watch Project Runway together. They make beautiful music together (literally) under the banner of Perfume Genius, a critically acclaimed experimental pop project that Hadreas started back in 2008. He actually signed the deal for his first record, Learning, in a blackout. (“Don’t do that, though.”) But all of the music on that record—and all of the records—has been created sober. That blue and pink and black velvety body of work is all range, from the “sober-y,” spare, and acoustic “Normal Song” to 2017’s delicate-to-symphonically-devastating “Otherside” to the horns-laced and dripping in David Lynchiness, “Photograph” from last year’s Ugly Season. And the last five Perfume Genius albums that they’ve worked on (yes, together) received the “Best New Music” marker from Pitchfork. The two are a contrast in working styles—Wyffels the morning-routined obsessive type, Hadreas the wait-for-the-inspiration-to-come-then-binge type. We talked about the beauty and horror of healthy codependence, the distinct odor of the fame hungry, and pushing the limits of recommended daily Diet Coke consumption.

What was the driving force that led you to sobriety?

Wyffels: Fear. I was getting into a lot of dangerous situations in blackouts that finally scared me enough. I’d gotten hit by a car running across the West Side Highway in a blackout. I had a bad night where I woke up with road rash all over my face in a stranger’s place. It just got to the point where I didn’t know where I was going to end up at the end of the day. I think fear of that is what got me there.

Hadreas: Eventually, the things I was doing became so distilled that I was actively thinking, “If I keep going, I’m going to die,” and just deciding that that was okay. And I would wake up thinking, “How was I there?” And then I’d end up there again really quickly after that. I didn’t really want to get sober. But I couldn’t keep going, either.

What does your sobriety mean to you?

Hadreas: The thing that shifted for me when I got sober—and stayed sober—is that I found a spiritual idea to help me find a way to have grace or feel okay that was just mine. It’s not an outside thing. It’s a feeling thing. It’s a nervous system thing.

Wyffels: It’s everything. Before I got sober I could not show up for life at all. I drank from the moment I woke up til the moment I went to bed. That was my life. Everything I had wanted to do with my life before that just stopped. I meet people who are suffering from their drug and alcohol use but can keep it together just enough that they don’t have to do anything about it. I’m grateful that I have no choice. If I wanted to have any sort of life, I had to get sober.

What are some of the pros and cons of being in a sober relationship?

Hadreas: It’s all pros, right?

Wyffels: I can’t think of anything bad.

Hadreas: I don’t know if I would’ve stayed sober if we hadn’t been together. There’s something beautiful about that and something scary about that, too.

Wyffels: I think the main pro is that you always have this person with you who keeps you accountable. You know that if you don’t stay sober, it’s going to jeopardize the relationship or jeopardize their sobriety. Sometimes if you’re not willing to stay sober for yourself, staying sober for someone else is good enough.

How has sobriety affected the way you make music?

Hadreas: I’ve only made music sober. I didn’t make music until I got sober. I didn’t write a song until the month after I got out of rehab. I like the music I made back then. I’m really proud of it. I feel like I’m always trying to get back to that. There was some alchemy. There was something simple. I had so much to say and I felt like I had found a way to say it in 3D.

Wyffels: Self-loathing is a big part of my alcoholism. When I’m in that, I don’t think I’m capable of doing much of anything. Until I pushed through that in sobriety, I didn’t believe in myself enough to even try. We’re kind of a weird example of sober creativity. We both didn’t really do anything before we got sober. I don’t think that’s very common.

Has sobriety altered your taste in music? Anything you left behind forever?

Hadreas: Yeah. Broadcast. For some reason whenever I was doing drugs with this one friend, he was always playing Broadcast. And always in that critical part of the night when it was really tense and really not fun anymore. I can’t really listen to that anymore.

Wyffels: That’s very true of music. I’ve walked into cafes where there’s a song on and my stomach drops. I’m like, “I can’t do this right now.” Music can take you back to a moment so fast—in a good way—but also in a really bad way. It’s kind of wild. You’re back in that moment with all the feelings around it.

Hadreas: A lot of things I remember about drinking and music were when it was fun, though.

Wyffels: There’s a lot of music that feels like drugs.

Hadreas: That’s cool, though. I like that. That’s okay, right? That’s allowed.

How has sobriety changed the way you collaborate with one another, others?

Wyffels: The ability to be present is really useful in making music and collaborating. When you get sober, you learn how to listen to other people, you learn how to communicate with other people, you learn not to think that you know everything.

Hadreas: 80% of making things is just doing it. I didn’t do anything when I was high. I had all kinds of ideas. But I was just sitting there thinking about them or talking about them. To make things with other people you need to go where you said you were going to go and then do it.

The music industry is notoriously booze-ridden and drug-addled. How do you navigate that?

Wyffels: That’s been the great thing about us being together. We’re not navigating it alone. I think that would’ve been brutal. It was hard at the beginning. People would stay up all night at festivals hanging out or go to bars after shows. In the early days, we weren’t really comfortable hanging in that way. There was this camaraderie element we felt like we were missing out on. That’s a real thing. You just have to find the other people who aren’t doing that. In any industry that is drug infested, there will always be a lot of sober people, too. Those two things go hand-in-hand.

Hadreas: It was hard when we first started. When I’d meet with the business people they’d be like, “What are we supposed to do with you? Just have lunch? Have some milk, or something?” It took us longer to feel bro-y with other people. At least in my head. Well, I did sign my first record deal in a blackout. I wrote all my music. And then I went out for a year. And somehow in that I got a record deal. And then I got sober again. And then I did everything. Don’t do that, though.

Wyffels: Don’t ever sign a record deal in a blackout. That haunted us in a bad way.

Given alcohol's well-documented effects on productivity, why do you think there continues to be so much stigma re: not drinking in creative industries?

Hadreas: I don’t understand why people think being able to drink a lot is tough or strong. It’s the same as people who drive really fast cars. The car is fast. Why would that be impressive to me? You’re not fast. It’s the same kind of thing.

Wyffels: It comes with the romanticizing of this wild, troubled, bad boy. It’s a cultural thing. Creative people seem to be prone to liking to check out or turn up. It’s encouraged. In the music industry it feels like people want you to be reckless. It’s hard to grow up in the music industry. Alcoholics are already stunted emotionally. Being in the music industry compounds that. There’s a major Peter Pan syndrome. It’s a hard industry to be an adult in.

Hadreas: All the books I read growing up were about tortured artists who were junkies or hustling. That’s what I thought I was going to do. So, when I was doing that, I was like, “I’m an artist.” But I was really just doing lots of cocaine and going out a lot. There’s this story that if you want to make something dark or f*cked up, you have to be depressed or high. For me, nothing has ever come from that. All of my darkest and most depressing sh*t I’ve made on antidepressants and sober. Some of the saddest things I’ve ever made have been when I’m the most content.

What’s your daily routine like?

Wyffels: I wake up. I start the coffee. I roll around on the carpet. It’s a somatic kind of thing. I pray and meditate. And then I get f*cking lit on coffee. I play the piano for a couple hours. I’m a morning person. He sleeps in. So, it’s kind of my time.

Hadreas: I don’t have one. I don’t know if I have any routines. I’m a binger. In order for me to make something, my brain needs to feel empty. After touring a record for a long time, it takes a while to clear everything out. It’s pressurized now because it’s our job. I have to sort through all the pressure and find some way to either use it as fuel or forget about it so I can go somewhere that feels mystical. It takes me a while. It’s always kind of sh*tty at first so I avoid it. But the avoidance is me clearing out my brain. And then I binge on work. I write every day. And that’s all I’m thinking about—even when I’m not doing it—until it’s done.

Wyffels: You firmly believe that doing nothing is part of the creative process.

Hadreas: I want what’s there to reveal itself. I don’t want to pick it. I can tell when I’m trying to make something happen instead of just letting things happen. There’s no formula to it. Sometimes I go in and it’s there. And sometimes I go in and there’s nothing.

What’s your go-to non-alcoholic beverage?

Hadreas: Diet Coke.

How many per day?

Hadreas: Is this on the record? Well, they did a study that says the max is 15 per day. So, it’s under 15.

Wyffels: I drink black coffee and water. That’s it.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Hadreas: “Maybe it doesn’t matter if you want to or not.” That’s been revolutionary for me. It doesn’t matter if I want to do a thing or not as a reason for doing it.

Wyffels: I have advice that I would give. I probably did receive it at some point. For artists, it’s always important to stay true to your vision and your artistic integrity and not let too many things come in and influence that. When you make art or music and you start to get an audience and start to see what people respond to and what they don’t respond to, there are these pressures. Maybe it’s a label or a manager that’s trying to steer you in a certain direction. People can smell that. You can always smell when somebody is hungry for attention or fame. They might have a blow up moment. But it might just fizzle out. When you stay true to what feels right for you, it’s more sustainable. That’s what I always tell people. That’s been true for us.

Hadreas: It sounds singular. You’re making choices from where you’re at. There’s a risk there for it to be bad or stupid. But when you can’t hear any conflict in something, that’s when it sounds boring.

Wyffels: I don’t mean don’t collaborate. Collaboration is amazing. Just don’t round off the edges of what you’re doing to make it more accessible.

In your mind’s eye, what is the shape of success?

Wyffels: I just want to make one solo piano record. If I do that before I die, I’ll be happy.

Hadreas: That’s it?

Wyffels: That’s it.

Hadreas: I feel like you have more than one record in you.

Wyffels: If I can just do one I’ll be happy. I’ll feel I’ve succeeded.

Hadreas: Well, that’s good.

Words by Andrew Smart / Photos by Roman Koval