LOST IN AN IMAGE

Chasing perfection and hoisted by our own personas

“There would be images all around them. Those images would be on the phone that woke them up. An astronaut singing in outer space. A girl riding a wrecking ball. They would light up their pillows as they roused from sleep, and parade, one after another, beneath their fingertips while they used the bathroom. They would be there in the kitchen on the tablet as [they] waited for their coffee to brew, then reappear seamlessly on their monitors in the home office. A jealous husband’s threats graffitied across the front of a house. Goats teetering on a cliffside or at the edge of a highway overpass. Whenever they went out for lunch, the images would shrink to the size of the rectangular screen and hover, midair, a foot above their plates. A tornado of sharks in the sky. While they waited for the U8 or the M29. While they took a piss. A famous woman spraying an arc of champagne backwards over her head into a wineglass balanced on her tailbone. Those images lit up their faces in the dark bedroom when they went to set the alarm. The faces of strangers. The faces of handsome criminals. Avocado slices.” —Vicenzo Latronico, Perfection

“Image is everything.”

Those of us of a certain age most certainly remember this famous slogan, delivered from behind lowered black Ray-Bans by Canon pitchman and tennis great, Andre Agassi.

If you’re like me, though, this statement is less a memory than a psychic tattoo. At the time of that advertising campaign’s running, I was an impressionable pre-adolescent likely watching The US Open with my mother, an Agassi gal all the way.

I wore his Nike Air Tech Challenge 2s. With the hot lava. I had his signature Nike jorts—my skinny legs far from filling the neon lycra lining sewn into the stonewashed black denim. If Andre said it, I believed it. And I also needed to work on my quads.

If you’ve read his fantastic memoir, Open, you’ll realize that the image really was everything. And by Agassi’s own admission it was empty. For one, for much of his career, Agassi hated tennis. For another, his long, acid-washed, feathered locks that I loved (and my father, a Sampras guy, hated) was a wig to mask his hair loss. Agassi recalls that “every morning [he] would get up and find another piece of [his] identity on the pillow, in the wash basin, down the plughole.”

Before the 1990 French Open final, this led him to pray. Not for victory. But for the divine hand that would keep his wig from falling off on live TV in front of millions of fans. Essentially, to remain unrevealed. To ensure that a self one less hairpiece closer to his authentic self would never be on display for all to see.

And he lost.

Years later—heart on sleeve and no hair on head—Agassi captured that elusive French Open title and completed “the career slam,” something his hirsute rival Sampras never accomplished. And he squared his relationship with the game.

In sobriety, we live by the credo “compare and despair.”

But what happens when the object of our comparison isn’t a world-class tennis player, or a model, or a recently promoted coworker, or a writer with more Substack readers? When we measure one version of “self” against an internalized ideal of one? When the ego becomes attached to an unattainable image (persona) of its own “curation?”

As Jung posits, “The persona is a complicated system of relations between individual consciousness and society…a kind of mask, designed on the one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and, on the other, to conceal the true nature of the individual.” Problems arise when we over-identify with it, losing the ability to decipher the difference between mask and face.

Despite being conditioned by “the culture” and its media to believe otherwise, we can’t actually find a Self in a persona.

We can certainly try. I certainly have. But to borrow from Hamlet, we all end up hoisted by our own petards.

We lose ourselves in the image.

In his biting novel, Latronico describes the Millennial condition as coming of age “with the notion that individuality manifested itself as a set of visual differences, immediately decodable and in constant need of updating.”

From a Jungian perspective, this is futility on a Sisyphean scale as “The more one identifies with the persona, the more individuality is suppressed.” Constant image tailoring and personal branding is effectively the antithesis of individuation.

I worked in advertising at the dawning of the Tumblr moment, when everything became image. Like Latronico’s protagonists, I could justifiably scroll through hundreds of images per day and call it “work” with little thought to what it might be doing to my brain chemistry.

How could it have occurred to me then that the seeming resistanceless fluidity of scrolling could create rigidity? And that that rigidity would be a source of resentment?

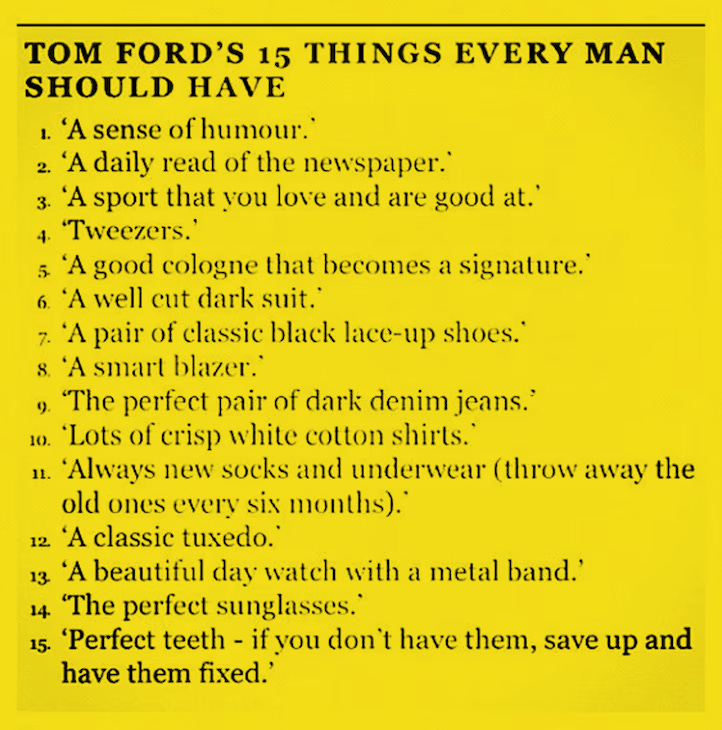

At about 30, I was still impressionable. Too impressionable. Parts of me stunted at the age I was when I started drinking. At that time, scrolling through Tumblr, I came across a list of “15 Things Every Man Should Have,” that (reportedly sober) Virgo paragon of persona (whom I admire tremendously), Tom Ford, came up with. On it—among other things—you’ll find: “A sense of humor, a daily read of a newspaper, [and] always new socks and underwear (throw away the old ones every six months).” And to this day, I am haunted by the possibility that I write these words in a seven-month-old pair of boxer briefs as unread newspapers pile up beside my bed.

Sure, I don’t pop molly anymore. But I still make vain attempts to hermetically rock Tom Ford’s list (and countless lists like it of my own conscious and unconscious creation). Because if I can force my own (visual) identity into a simple construct—any construct—it might mollify the unbearable pain of living out any day at any distance from my authentic self. (It doesn’t).

Advertising clients are always begging for images of authenticity. But isn’t that an oxymoron? Aren’t all images essentially inauthentic by definition? Near representations of reality, sure. Especially when captured on film (maybe even on a Canon EOS Rebel). But never reality.

Reality isn’t capturable. Nothing is. In this fleeting life of temporary joys and pain, all things pass. As soon as we grasp it, it slips through our fingers. It’s gone.

Youth fades.

Hairlines recede.

Our children are like trains that leave the station the moment they take their first breath and never return.

And sobriety is a daily reprieve that renews every morning. One to be “worn like a loose glove.” More so, perhaps, if the glove you have in mind has a Gucci label sewn into it.