TOO DRUNK TO F*CK

A somewhat scientific study of sex in sobriety

When I first got sober, there were two questions that haunted me. How will I eat sushi without a big Sapporo? And how will I have sex? With anyone. Ever again.

Like many folks—addicts or not—I had relied on alcohol as a kind of courage lubricant in the sex sphere. Without it, I was painfully self-conscious and reserved. With it, I could be a f*cking freak. Or that’s—at least—what it would have had me believe.

Until I got sober, I had never had sex with a new partner for the first time without being under the influence of alcohol. I couldn’t imagine initiating the act without it. In an effort to avoid that awkwardness, I thought it would be #monkmode and a life of celibacy for me.

I was wrong. But looking back, I wish someone had said, “Actually, in all likelihood, you will have less sex with fewer partners. But you will have sex. And it will be more satisfying. And you’ll feel less guilt and shame about it afterward.”

After somewhat scientifically surveying dozens of sober folks, that seems to be the case. For most. And these were folks who—before sobriety—liked to get drunk to get down. About 80% of respondents claimed they were “always” or “almost always” under the influence when they slept with a new partner for the first time. Perhaps this is just a force of habit. I imagine the general population might be more prone to being under the influence when hooking up than when doing just about anything else. As William George, director of University of Washington’s George Lab (that studies the influence of alcohol on sexual health behavior) writes, “sex is rewarding, and alcohol has salutary aspects; there is a reason why the two activities have been joined through most of human history and known prehistory.”

A lot of addicts, of course—when awake—are always at least a little f*cked up, whether they’re f*cking or the farthest thing from it. For them, always or almost always might apply to things other than sex. Like watching the Lakers. Or driving to work. But for those who weren’t wasted all the time, the relationship between alcohol and initiating sex with a new partner was deep if not totally inextricable.

Reflexively, the alcohol-sex link must be chalked up to the link between alcohol use and disinhibition, right? Conventional wisdom posits that alcohol’s aphrodisiac qualities (if it has any) are related to the disinhibition mechanism. However, evidence supporting the disinhibition concept is “modest” and it can be perceived as a “far from well thought out pseudoexplanation.”

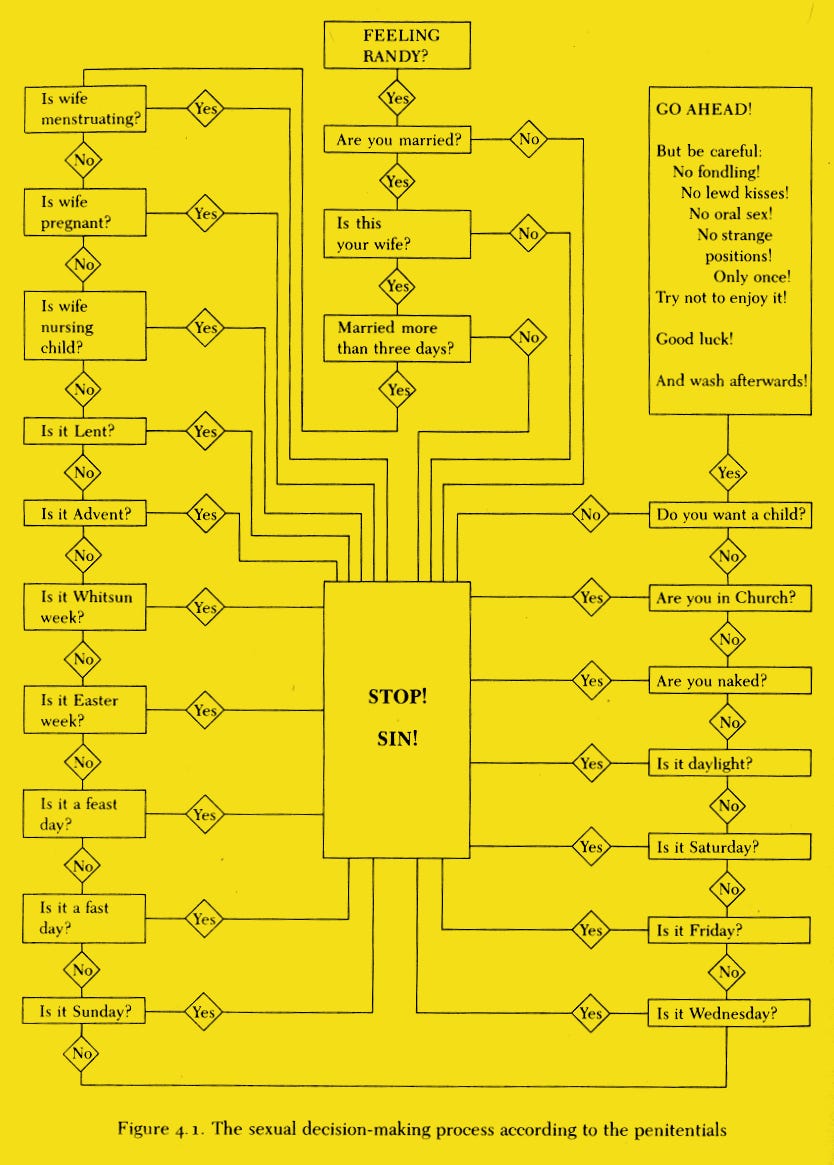

Furthermore, “inhibition” (or any of its synonyms) weren’t words that came up in the survey. Curious, perhaps. But in 2025, inhibitions that are “culturally inculcated” or “externally imposed” are fewer and farther between. For many, there is less to be sexually inhibited about now than there has been for the past several hundreds of years of western, Judeo-Christian history. See: d*ck pics, for one.

William James, the so-called father of modern psychology called inhibition “an essential and unremitting element of our cerebral life.” Inhibition might be defined as “an individual’s tendency to limit behavior leading to adverse outcomes.” Gone awry, of course, such limiting behaviors can verge into the territory of neuroticism. And neuroticism itself is “a risk factor for heavy alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and binge drinking.” Sometimes the tail wags (the hair of) the dog.

A more contemporary reading of inhibition might view it as a goal rather than a process, i.e., people don’t “do” inhibition, they don’t "use inhibition to suppress a target response.” Instead, the purpose of inhibition and the strategies employed to arrive at it (strategies perhaps compromised by the pharmacological effects of alcohol) is actually achieving one’s goals. Such a definition might seem anathema to a culture that often perceives inhibitions as an impediment to the achievement of goals. That makes for a good Hollywood plot line. But inhibition—like ego—gets a bad rap in a rampant consumer culture where we’re indoctrinated to “always be closing.” As one respondent reflected, drinking has the capacity to “turn on the confident sales pitch” version of ourselves. The choice of words, “turn on,” does not go unnoticed here. It’s about living out an idea of sex more than a lack of inhibition. As George writes, “an individual’s sexuality after drinking is mostly a product of their beliefs about alcohol and sex, beliefs based on previous personal and vicarious experiences as well as culturally acquired schemas.” In short, after drinking, people behave how they believe they’re supposed to behave after drinking. They turn it on, living out “self-fulfilling prophecies about what is expected from alcohol as an excuse for out-of-character behavior.”

“To thine own self” be damned. Even the mere presence of alcohol—without even ingesting it—makes people see potential sexual partners where there might otherwise have been none. What behavioral psychologists call “alcohol expectation theory,” the rest of us call “beer goggles.”

In practice, “turning it on” to secure a new sexual partner might actually be in conflict with our actual nature. From an evolutionary standpoint, the goal of sex is to mate at the highest standard. It makes sense to choose wisely. And this is especially true for women who—if made pregnant by a questionably DNA’d degenerate for nine months—would be incapable of procreating with a better mate for the duration. And life is short.

Alcohol, of course, helps many suffer fools lightly. Without it, as one respondent mentioned, they “think twice” about who they’re going to invite back to the crib. From an evolutionary perspective, abstaining from alcohol seems to push people from short-term to long-term mating strategies. In other words, moving away from “hit it and quit it” encounters (primates do this) or one-night stands with unavailable fuccbois (primates do this) in favor of experiences that require “investment” and “exchange” (primates do this, too).

This aspect of discernment or intentionality is reflected in the 75% of respondents who claim to have fewer sexual partners in a given year of sobriety than they did before getting sober. It’s fair to say that sobriety makes many more selective: ideologically, aesthetically, and Darwinianly.

Also, it’s likely that sobriety is a gateway to committed, monogamous relationships. Practicing alcoholics often don’t make the best life partners. Trapped in a narcissistic feedback loop, many lie and cheat and steal and put using ahead of all relationships, sexual or not. Given the majority of respondents claimed to be in committed monogamous relationships, it would seem there is a positive correlation between sobriety and monogamy. Especially for sober men, over 70% of whom reported being in monogamous relationships. (This is slightly higher than the national average according to the Pew Research Center).

One thing the survey did not account for is the possibility that some people have no sexual partners at all. For some, no sex could be more satisfying than any sex. For others, a fear of intimacy, social awkwardness, or body shame—once subdued by the pharmacological effects of alcohol—might lead to difficulties with sex (or the desiring of it). As one respondent stated, “I never realized how much I relied on substances to engage sexually. Without them, I find it hard to even think about it.” Sexual anorexia, “a concept that refers to the compulsive avoidance of sexual nourishment and intimacy,” could be a real danger in sobriety if the denial of “pleasure” associated with abstinence from drugs and alcohol mutates into compulsive self-starving of “the pleasure of relationships, dating, loving touch, and genuine connection with others.”

While sober people are having sex with fewer partners, they are also having less sex period. Only 20% of respondents claimed to have more sex in sobriety than they did before. 50% of men report having less sex. Women, 70%. This might be explained by factors that can affect all people—monogamy, raising children, the pandemic, stress, aging, etc. Or, sober folks might be missing the libido bump derived from “modest consumption up to a blood-alcohol level of around 0.08 percent.” While 66% of singles reported having less sex in sobriety, only 50% of those in committed relationships reported having less sex.

The sex they are having, though, is generally perceived to be more satisfying. And some reported actually remembering it being a factor. Only 16% of those surveyed found sex to be less satisfying in sobriety.

While drinking and sex are frequent bedfellows, they aren’t necessarily happily compatible ones. For men, “chronic high alcohol consumption is linked with impaired erectile functioning and associated sexual dysfunctions such as erectile disorder, hypoactive sexual desire, and either premature or delayed ejaculation.” For women, “heavy alcohol use is related to impaired sexual functioning, including lowered sexual interest, desire, and satisfaction, as well as lack of orgasm and lubrication and painful intercourse.” Has an unsexier paragraph ever been written? Certainly not by me. And that’s just the biological factors.

Of those surveyed, 60% of respondents reported experiencing “less” negative thoughts or feelings like shame or guilt about their sexual experiences in sobriety. 20% responded “about the same.” And only 16% responded “more.” It’s possible this is the result of having less partners and less “casual” sex in sobriety. “Feelings of embarrassment, loss of self-respect and sexual regret are common” after a hookup. Furthermore, “relative to romantic partnerships, casual sexual experiences are associated with more negative emotions, such as negative affect and guilt.” Thoughtfulness, presence, intentionality, and consciousness—words typically associated with experiences spiritual rather than sexual—appeared multiple times in survey responses. Across a variety of genders, sexual orientations, and relationship statuses, sobriety seems to imbue sex with something akin to a spiritual experience. And that seems to be the best hedge against feelings of guilt and shame.

In conclusion, for those who do choose a life of sobriety, their sex lives will likely change. Significantly. And for the better. Change—per usual—is life’s only constant. For many, sobriety is a spiritual practice. And that practice applies to all facets of life. Even sex. Or perhaps, especially sex. At the risk of stating the obvious, the most significant difference between sex before sobriety and after sobriety that the survey captured regarded the percentage of people who never slept with a new partner without being under the influence. Before sobriety, that number was zero. After sobriety, that number is 100%. From a data perspective, there is no greater possible divergence. And, it would be interesting to see where else in sober lives—outside of the sex sphere—the degree of the change would be that significant. Even sushi and beer. Upon further reflection, an iced green tea did on occasion do in a pinch with a spicy tuna roll taken at my desk at the office. And it still does. Even at Sushi Gen. Or perhaps, especially at Sushi Gen.